Abi Bush, Manufacturing Engineering graduate (2014) from the Institute for Manufacturing (IfM), was based in Nepal in 2016, and works for non-profit organisation Field Ready.

Through working with Field Ready, I have seen how the way we currently manufacture products leaves us vulnerable to crisis. When transport infrastructure and communications infrastructure is damaged, international supply chains are not as effective as one might hope. In many more cases than I originally thought, making things locally is quicker and cheaper, and more responsive to the needs at hand.

Abi Bush (MET MEng 2014)

The organisation meets humanitarian need by providing solutions in health, water and sanitation using new technologies such as 3D printers and laser cutters as well as conventional manufacturing techniques.

Abi, Engineering Advisor, was based in Nepal last year and has been working on a number of different projects with Field Ready following the devastating earthquake, including 3D printing low-cost medical equipment and replacement parts for clinics that lost much of their equipment in the earthquakes. In another Nepalese project, she has been working with a local design entrepreneur to help him to develop improved wood-fuel cooking stoves that reduce people’s exposure to harmful chemicals in smoke.

We caught up with her to find out more.

Why did you decide to study manufacturing engineering?

When I set out at university, I really wanted to learn how to design great products. Part of that was understanding the physics underpinning how things work, which is covered on the main engineering course. However, there is a lot more to designing a product than the math – there is how it will be made, who it will be used by, the impact a product will have throughout its lifecycle and, of course, getting your hands dirty and prototyping. Additionally, I think it is increasingly important for engineers to be able to make informed decisions about how and where products are made, from social, environmental as well as economic perspectives. The Manufacturing Engineering Tripos (MET) course is one of the few ways to explore this wider perspective.

Tell us about how you came to join Field Ready?

I used to volunteer with Engineers Without Borders while I was at university and through that network heard about this amazing organisation called Field Ready which was trying to change how aid is delivered. Fortunately, I was successful in my application for the Nepal programme.

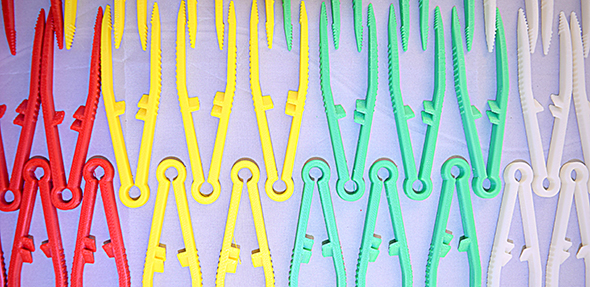

An example of 3D printed medical tweezers. Credit: Field Ready

What projects have you worked on or are currently working on at Field Ready?

During my time in Nepal, my work was quite varied, but I did end up doing quite a bit on developing 3D printable medical supplies.

Many aid agencies are working to provide assistance to clinics and health posts that lost a lot of their equipment in the earthquake, but they face some major challenges given the specialist nature of medical supplies. For example, many of the more sophisticated pieces of equipment donated by aid agencies break under the tough environmental conditions and it can be very difficult to get spare parts. This is because the donated items typically come from very far away, so it is expensive to ship spares, and the equipment tends to be quite dated so spares may not even be available.

Often, we would go to a health clinic and find equipment that wouldn’t work because, say, a plastic connector was broken, and the clinic would be unable to fix the problem without having to buy a completely new piece of equipment. At this point, a laptop and a 3D printer become a brilliant resource to design and print replacement parts on the spot.

Sophisticated equipment aside, even simple and basic supplies were taking aid agencies three to four months to procure from places like India and Germany. This inspired us to start work on 3D printable medical devices, such as otoscopes, kidney trays and tweezers.

We are testing this model right now with a number of our designs and a 3D printer travelling with a doctor around a few remote clinics in Nepal.

What does an average day look like for you?

Much of my day is spent on either the CAD design software Solidworks, with a pen and paper exploring new ideas, or with a 3D printer prototyping and making.

Something that might be more surprising is that an average day in the field can typically involve a lot of calls and meetings. This is for both internal and external reasons. The Field Ready team is distributed over nine countries, so it takes a bit of work keeping up with what everyone is doing and making sure we are all heading in the same direction.

Externally, we are always talking to different potential partners and exploring the supply chain or quality challenges they have to see if we can help. Additionally, for every design we make we need to seek user feedback, especially with more critical devices such as medical products. In Nepal, where transport is tricky, we could spend an entire day just travelling to reach the people who are using our products so that we can check that everything is still working well.

Medical professional uses one of the 3D printed otoscopes to examine a patient’s ears in Nepal. Credit: Field Ready.

What is the most rewarding experience you have had at Field Ready so far?

In Nepal, we completed a piece of work for a local entrepreneur (Madhukar KC) who makes and installs clean cook stoves (biomass stoves that produce less smoke). The key to his design is an improved burner that enables more oxygen to get to the burning wood. He has been iterating on this concept for more than 10 years, by carving wooden patterns by hand, then giving the patterns to a sand-casting factory to manufacture in cast iron. However, when we met him he still hadn’t quite reached the government requirements for cook stove performance, which was limiting the growth of his business.

He had an idea for a design that could do it, but it was too complex for him to make by hand in wood. My colleague Ram spent a couple of days with him turning his idea into a 3D computer model and then we printed out his design.

Since then, the new stoves made from our 3D printed pattern have passed the government requirements enabling Madhukar to win contracts for more than 200,000 stoves. It was really exciting for me to see the huge impact just a single 3D print can have, particularly through working with local innovators and manufacturers. That 3D print has improved Madhukar’s business and the sand casting manufacturer’s business, in addition to all the customers who benefit from cleaner cook stoves. We have also increased the likelihood that aid agencies will buy locally rather than importing from elsewhere.

Has Field Ready changed the way that you look at manufacturing engineering?

Definitely. For me, the idea of distributed manufacturing has gone from a neat academic concept to an essential paradigm shift for the future. Through working with Field Ready, I have seen how the way we currently manufacture products leaves us vulnerable to crisis. When transport infrastructure and communications infrastructure is damaged, international supply chains are not as effective as one might hope. In many more cases than I originally thought, making things locally is quicker and cheaper, and more responsive to the needs at hand.

Much of the exploration of distributed manufacturing in the academic world is focused on the circular economy and sustainable cities; the idea of flexible machines capable of making a wide range of products in one place, coupled with digital supply chains where information, not goods, travel around the world. This means the skills needed to manufacture goods would be embedded at a local level, not just an international level. For me, distributed manufacturing is about resilience, not only against major humanitarian crises, but also the social crises we are seeing due to the collapse of companies and industries in particular localities.

What is the most useful advice you could offer someone who wants a career where they can make a positive difference?

There are a million ways to make a positive difference and the answer isn’t always to try and match your skills to what is typically perceived as this. Effecting positive change in the world can often start with positive change in yourself: through developing your skills, your sense of self and enthusiasms, you will only increase what you can offer to other people in the world, no matter if you are working for an NGO, a university, a carpentry shop or a bank. Finding out what skills and passions you want to develop is of course somewhat harder than it sounds, and it takes a bit of experimentation.

What’s next?

I’m concentrating on some of the challenges we are seeing coming out of the Syria crisis. Given that these are developing countries, the challenges are technically a lot more demanding than others we have seen.

What is your biggest passion outside engineering?

I love adventure sports; living in Nepal last year was great for trying a few new things such as trekking and white water kayaking. However, being back in Europe (currently Paris) has given me an excuse to get back to skiing, and I enjoyed a week learning to ski off-piste earlier in the year.

This article has been edited from the IfM website.