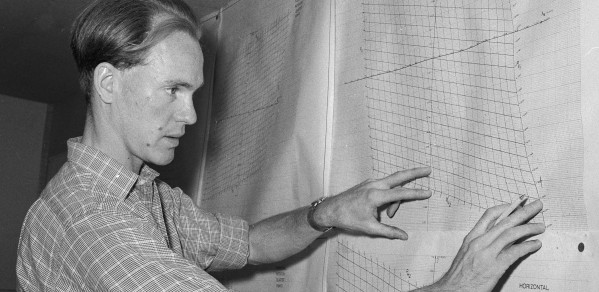

Alumnus Tony Gee had his 15 minutes of fame towards the end of 2014 when the 50th Anniversary of the opening of the Gladesville Bridge was celebrated in Sydney, Australia. Tony tells the story of how he came to be the designer of the Gladesville Bridge below.

The circumstances which led to a raw graduate being responsible for the detailed design of a record breaking bridge seemed unexceptional at the time and it didn't really sink in until later just how fortunate I had been.

Alumnus Tony Gee

Although not particularly well known in the UK, Gladesville Bridge was the longest concrete span in the world at the time it was built, a distinction it held for a further 7 years. The New South Wales personnel who were organising the 50th Anniversary celebrations asked Structurae, the largest database for civil and structural engineers, whether they could find any record of the designer of any other major bridge being around to celebrate its 50th Anniversary: the nearest they could come up with was Othmar Ammann, the designer of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge in New York, who lived for 33 years after its opening.

Needless to say, Gladesville Bridge holds a very special place in my life. The circumstances which led to a raw graduate being responsible for the detailed design of a record breaking bridge seemed unexceptional at the time and it didn't really sink in until later just how fortunate I had been.

My boss Guy Maunsell had returned from Australia with his concept for a big concrete arch and needed someone to work with him on the realisation of his dream. It had to be done as inexpensively as possible because it was viewed as somewhat of a long shot and the recent graduate recruit was the obvious choice! It was only after the design was finished that I realised what an incredible opportunity it had been.

I am sometimes asked how bridge design then differed from now. Two words - codes and computers. Design specifications were very basic; from memory, the Department of Main Roads bridge code ran to about 40 pages and the UK one was only slightly longer. The current version of the US bridge design specification contains 1,638 pages. We had to design almost everything from first principles and since several aspects of the design were not addressed in any of the specifications, this allowed us a latitude not available today.

Although a limited number of main frame computers existed, there were no commercially available engineering programmes so we had to write our own. The potential benefits of computerisation outweighed the effort of learning basic programming and ultimately all aspects of the analysis and detailing of the arch were executed using application programmes specially written for the purpose.

The people of Sydney should be extremely proud that they live in the only city in the world where a bridge like Gladesville could be overshadowed by - or at least have to share the limelight with - two other iconic structures. It was and still is by any standards a great bridge, not only because of its record breaking span - and there have only been 6 larger concrete arches built in the intervening 50 years - but because it featured a number of design innovations which have since been widely adopted. It is greatly to the credit of the former Department of Main Roads that they had the courage, open-mindedness and generosity to accept an alternative design which stretched the boundaries to such an extent that it gave them plenty of cause to reject it had they been so inclined.

It is extremely gratifying to see this 50 year anniversary receiving well-merited attention. It is also a sobering reminder of the passage of time! However, Gladesville is so soundly constructed and in such good condition that I see no reason why it should not remain functional for another 50 years and I look forward to gazing down in 2064 on our descendants celebrating the centenary of one of the world's great bridges. The bridge has recently been recognised as an “International Historic Engineering Landmark”.

Tony Gee Designer of the Gladesville Bridge

Tony founded the consulting engineering firm of Tony Gee and Partners in 1974. He retired from the practice in 1988 to live and work in the United States but the firm continues to thrive: it is now over 400 strong and was named “Medium Size Practice of the Year” by New Civil Engineer in 2013.

At the time of his later ‘retirement’ in 1995, Tony believes he was the only – and probably the last – person to be FICE, FIStructE and FIMechE.

He was a two-term Member of Council of the IStructE and a Founding Member of Council of the Steel Construction Institute.

He won an Oscar Faber Medal at the IStructE, a Telford Premium at the ICE and finally, in 1992, the Telford Gold Medal, the highest award of the Institution at the ICE.

Although he refers to his ‘retirement’, he is still doing some consulting and is currently working on the design of the first commercially viable maglev transportation project, having been involved in the development of the system for the past 20 years.

Alumnus Julian Gray of Clare College has written in to share his experiences working with the computing power of the 1950s:

After I left school in 1958 I had a couple of years before being able to take up my Cambridge place at Clare because of the queue for entry caused by the ending of National Service. I got a virtually unpaid job as an office boy with G Maunsell and Partners, the same firm [of Tony’s], who had an office almost next door to Clarence House and St James’s Palace round the corner at the bottom of St James’s Street.

In between doing useful chores like going to Victoria Street to obtain prints of huge concrete bridge designs destined for being built in Australia, with help from my faithful slide-rule inherited from my mining engineer father and some tatty log tables, I did some fascinating odd calculating jobs and also a few tracings of engineering drawings with Indian ink.

After some weeks I got involved on the absolute fringes of the design of the Hammersmith Flyover. My bit of very low-brow low-risk work was to involve millions of calculations, and my “boss” at Maunsells made a ground-breaking suggestion that we should try to get some computer power to help with the task. That involved going to somewhere north of Oxford Street where there was a smart house that was home to a Ferranti Pegasus computer. We had a program composed on hundreds of punched cards and were duly delivered with our results on a large pile of printout paper – that was the way things happened then. I was able to summarise the output and to show that the design of the concrete upside-down coat-hanger-shaped concrete beams that supported the Hammersmith Flyover roadway was OK!

After my degree I used the same slide-rule and log tables for real mechanical engineering until the later 1960s when the first hand-held calculators were available. I still have the slide-rule, in its tatty old green box.

After my degree I used the same slide-rule and log tables for real mechanical engineering until the later 1960s when the first hand-held calculators were available. I still have the slide-rule, in its tatty old green box.

The Gladesville bridge in Sydney is an iconic structure, as Tony Gee says, and in my humble role as assistant apprentice unqualified ‘engineer’ I am still pleased to have been involved in using rare 1950s computer power for the equally iconic Hammersmith Flyover.