He never intended to take a PhD — or to present television documentaries. Dr Hugh Hunt, Reader in Engineering Dynamics and Vibration, is an all-rounder who combines his interest in things that bounce and spin with a passion for music and mending things.

It’s vital to share your enthusiasm. By jumping in at the deep end, I learned that I’m quite good at getting young people excited about science and engineering.

Dr Hugh Hunt

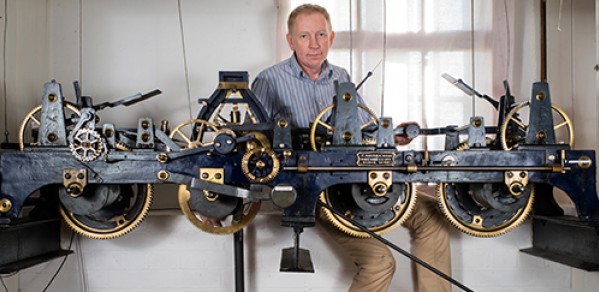

At Trinity College, I’m Keeper of the Clock. The clock tower is one of the oldest parts of the college. The bells you hear striking every quarter of an hour date from 1610. The current clock mechanism was installed in 1910. It has a double three-legged gravity escapement. Someone has been looking after Trinity’s clock, winding and resetting it, for more than 400 years. For now, that person is me — with help from many others. Follow @clockkeeper on Twitter!

We need to look after things. With climate change, we must learn to be more resourceful and extend the lifespan of the stuff we own. To fix things, you need to understand how they work. If a key jams on your keyboard, instead of chucking it out, you can take it to bits. As Dame Edna Everage said about fashion: why throw it away, possums, if you can still wear it?

I’m fascinated by things that bounce and spin — the dynamics of rigid bodies. Back in 1999, Professor Mark Warner and I were invited to give a lecture called 'Spinning into Space' for National Science Week. We did lots of on-stage experiments and won an Institute of Physics award. Requests to do more lectures poured in.

I’ve learned to say yes to invitations — especially for outreach events. It’s vital to share your enthusiasm. By jumping in at the deep end, I learned that I’m quite good at getting young people excited about science and engineering. I give lectures to audiences of up to 800, organised by initiatives such as Maths Inspiration and The Training Partnership. My talks have an element of chaos but, like any pantomime, it’s all well-rehearsed.

My props include bouncing balls and boomerangs. Over the years I’ve acquired dozens of objects that help me demonstrate the basics of spin and angular momentum. When I took the train to Cardiff in December to give a big Maths Inspiration show to 15- to 18-year-old students from Welsh schools, I took a large suitcase full of toys and a couple of rugby balls just in case.

Hugh Hunt with replica BE2c biplane used to shoot down Zeppelins (Credit: Hugh Hunt)

Public lectures paved the way to television appearances. In 2011, I researched and presented the two-hour Channel 4 show Dambusters: Building the Bouncing Bomb. It was watched by an estimated 5 million people and won a major award. I also presented a programme about the design of the Zeppelin which terrorised the British population in the First World War. More documentaries are in the pipeline.

I grew up in Melbourne, Australia. Dad was an engineer professor but more interested in theoretical mechanics than in making things. I was a bit different: I made all kinds of things starting with rabbit hutches and progressing to a complete refurbishment of the garden shed, including the electrics — which is how I learned the hard way about health and safety.

Music is important to me. I’m one of five children and we all played instruments. Mine was the French horn. I studied engineering at Melbourne University but being part of the Choral Society was what I enjoyed most. It made me realise that it’s important to do something you love doing.

I didn’t plan to do a PhD. When I graduated I went to work for an engineering company in Melbourne. At the end of my first year there was a party. One of my former professors came up to me. In that blunt Aussie way, he said: “Hunt, you’re an idiot, you should be doing a PhD.” Two weeks later, application forms from Cambridge University arrived in the mail. I guess he’d asked for them to be sent to me so I filled them in. Peter Joubert, if you’re reading this, thanks!

For 20 years I’ve been working on how to make trains quieter. The CrossRail project in London is brilliant. I think you’ll find the trains are quiet and the ride is smooth, which is good news for those living and working up above. There are lots of hotels, hospitals and recording studios along the route of CrossRail. The PiPmodel that I’ve been developing with some great students has been very useful.

My current research includes looking at ways of cooling the planet. I got into this through a project called SPICE (Stratospheric Particle Injection for Climate Engineering). SPICE investigates the benefits, risks, costs and feasibility of Solar Radiation Management through the deployment of reflective aerosols in the stratosphere. It’s all pretty scary, but if we do nothing we face desertification, flooding and sea-level rise.

Another geoengineering project has caught my attention recently. How can we extract non-CO2 greenhouse gases — such as methane and nitrous oxide — from the atmosphere? These gases are almost as important as CO2 for climate change and they are easier to dispose of. But we have to come up with a way of handling about one cubic kilometre of air per second if we’re going to make any meaningful difference. We need to be doing the research now.

Cambridge is on a continuum. My rooms at Trinity look on to the Great Court where they are part of buildings that date from the 1650s. Most evenings, as I close my door to go home, I have a sense of the people who’ve come before and those still to come. That’s the thing about Cambridge — we might think it’s ours but we don’t own it. We’re simply part of a continuum.

This profile first appeared as part of the University of Cambridge's This Cambridge Life series.