In a unique experiment, Dr Hugh Hunt re-staged the very first official broadcast on British television for BBC4 documentary ‘Television’s Opening Night: How the Box Was Born’.

In 1936, there were perhaps only 300 television sets in existence, but hundreds of people flocked to Selfridges in London to watch TV in the department store showroom.

Dr Hugh Hunt

Tomorrow (March 17), Dr Hunt will share the story of John Logie Baird, his 'flying spot' camera and the curious cast that made up that first primitive night of television, as part of the Cambridge Science Festival.

Free to attend, the talk will run from 5.30pm-6.30pm in the Mill Lane Lecture Rooms, 8 Mill Lane, CB2 1RW. Booking is required. Call 01223 766766 or visit www.sciencefestival.cam.ac.uk/events/first-night-television.

Here Dr Hunt, Reader in Engineering Dynamics and Vibration, writes about the history and the engineering behind that first live scheduled TV broadcast.

This is the story of John Logie Baird, the brains behind the first live scheduled TV broadcast by the BBC on 2 November 1936. It was a remarkable event because it had become a competition. The Scottish-born Baird’s 240-line mechanical system was pitched against the American 405-line EMI Emitron. The live broadcasts were transmitted from Alexandra Palace in North London. The Baird and EMI systems were in adjoining studios and on the opening night the Baird system went first – on the toss of a coin.

In 1936, there were perhaps only 300 television sets in existence, but hundreds of people flocked to Selfridges in London to watch TV in the department store showroom.

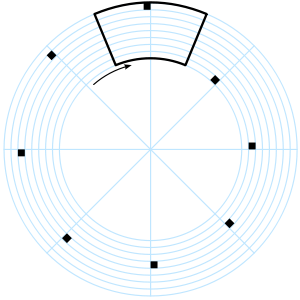

Nipkow disk

Nipkow disk

What is television?

Back in 1936, about half of households had a radio or ‘wireless’ as it used to be called. The BBC began its first wireless radio broadcast in 1922. Sound back then was transmitted in mono; the quality wasn’t great, but it worked.

Meanwhile, Logie Baird was working out a way to transmit moving pictures along with the sound – also by wireless. He made use of a Nipkow Disk, invented in 1884, which has holes in it on a spiral. When it spins, a bright light shining through one hole at a time causes a tiny spot of light to scan across the presenter's face. Hence the camera was known as 'the flying spot'.

Light reflected off the presenter’s face (who was sitting in a completely dark room) was picked up by a photocell and the reflected light intensity was relayed by wireless to television sets in people’s homes. The challenge was to recreate the images in a television set either by using another spinning disc (which was rather difficult) or by using a cathode ray tube so that a flying spot of light could be recreated on the screen.

Synchronizing the flying spot

Synchronizing the television’s flying spot with the camera’s spot was not at all easy and it took Logie Baird more than 20 years to perfect the system. The way the system worked was that at the end of each line there was a black band. The TV set would get a signal to know when to start the next line and at the end of each frame there were a few blank lines so that the TV could shift the beam back up to the top of the screen. There were many experimental broadcasts during the lead-up to the 1936 first broadcast and plenty of enthusiasts were tuned in at all hours of the night to see if they could pick up images. It was a great time for budding techno-nerds!

For the BBC documentary, we recreated an original flying spot camera. Our disc is 600mm in diameter with 60 holes spinning at 900rpm. This creates a 60 line image at 15 frames per second – not quite up to the original 240 lines at 25 frames per second, but we didn’t have 20 years of development time available. Still, our image quality was remarkable.

The box in action

The box in action

The opening night was recreated accurately with the script, music and acts almost exactly as they were broadcast in 1936. A peculiarity which we re-enacted was the 54-second delay necessary between the then old-fashioned static camera system used for filming in natural light. So our presenter, sitting in his darkened box, had to wait for 54 seconds before speaking after the orchestra finished playing the previous item and then the orchestra had to start playing 54 seconds before the presenter stopped talking. All truly bizarre.

The competition became a bit of a farce and it was halted after only a few weeks. The EMI Emitron system was so much more flexible and versatile than Logie Baird’s flying spot – it could film in natural daylight for instance – and the future of television was set. It wasn’t until the 1990s that flat-screen technologies became commonplace. Up until then all TV cameras were essentially a derivative of the EMI system and all TVs in our living rooms were cathode ray tubes. It’s sad that technologies come and as go, but as remarkable an invention as it was, I don’t think the flying spot was ever going to last.