Diana Thomas-McEwen believes in learning by doing. She trained as a marine biologist but always thought she could have been an engineer. After six years working in the oil and gas sector on survey ships, she took a change of direction.

My job is all about encouraging students to learn new skills and try their hand at something unfamiliar. Failure doesn’t matter. Our students learn fast and come up with some fantastically creative ideas. I sometimes have to stop myself from being overly excited.

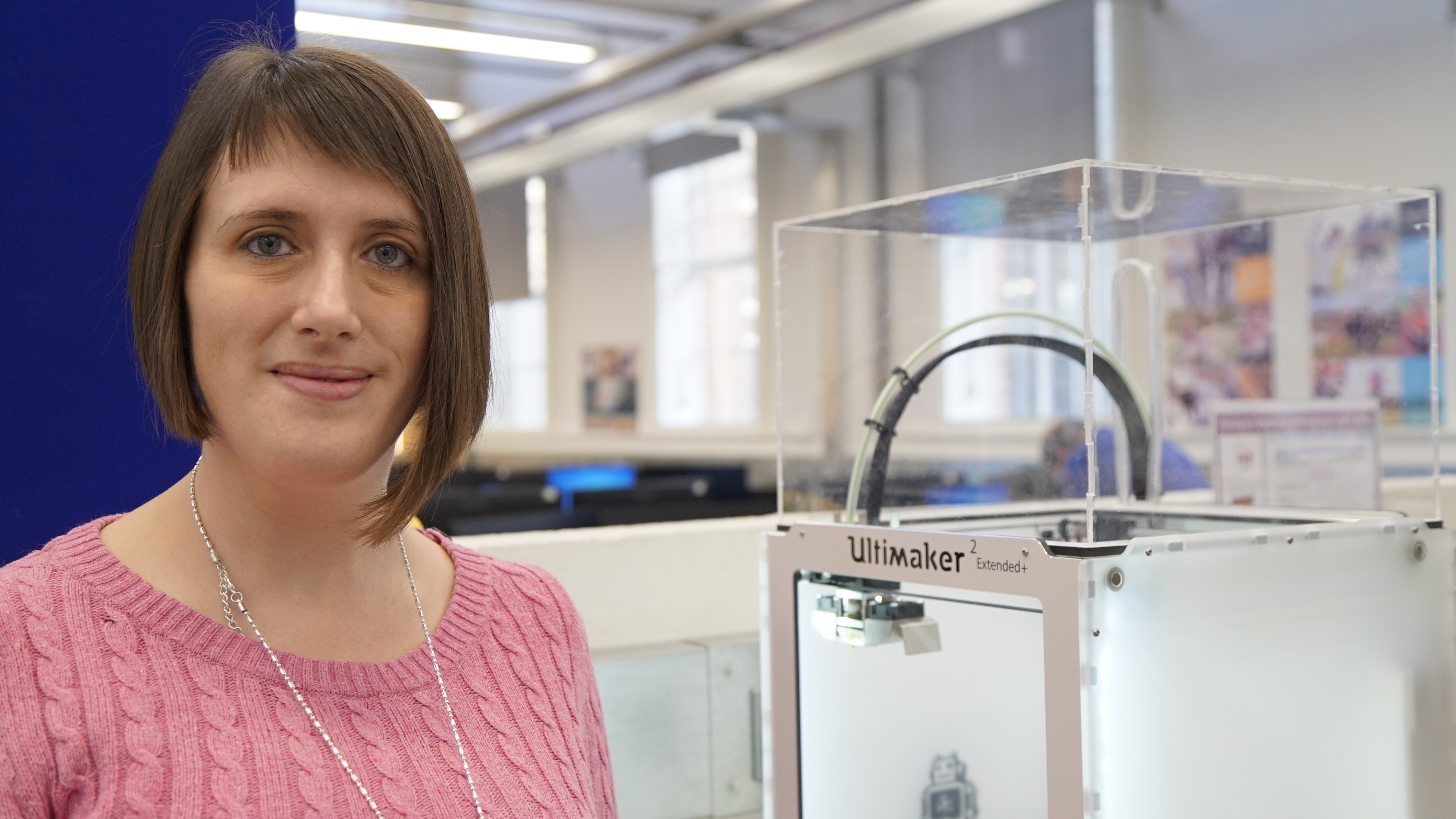

Diana Thomas-McEwen

Water is my element. But two years ago I made a big decision. I swapped my life offshore for a career on dry land. When I was little, my mum channeled my excess energy by taking me swimming. In my teens I trained as a lifeguard and a swimming coach.

Today I’m chief technician in the Dyson Centre for Engineering Design. We’re a team of five and we train students to use equipment that ranges from 3D printers to laser cutting. When we’re not running training sessions, we’re on hand to help students to create anything they come up with.

My obsession with water began when I was five. I’ve always loved the sea and the beach but it really took off when I was 15 when I saw a Comb jellyfish on a television series called The Blue Planet - The Deep (2001). Right away, I wanted to know as much as I could about these remarkable and stunning creatures.

On a trip to the USA, I went to the Monterey Bay Aquarium. I saw many wonderful animals including a lion’s mane jellyfish and sea otters that fueled my ambition to become a marine biologist.

My goal of becoming a marine biologist wasn’t supported by my teachers. I’d been diagnosed as dyslexic, rather late on, and they told me I’d never get to university. My mum, who is five-foot-nothing, stormed into the school and told them I could do it.

I was proud to have my parents’ support as the school wouldn’t listen to me. My mum stepping-in to put them straight, insisting that I could do this, was what I needed, an adult voice in my favour.

I passed my school exams and went to Essex University to study marine biology. During my undergraduate and masters studies, I took two trip to Indonesia to study coral ecology. I learn to Scuba dive and dived on a pristine coral reef. Later I visited the S.E.A. aquarium in Singapore with its mesmerizingly examples of jellyfish.

After university I got a job as a marine biologist with an oil and gas company. I went out on survey vessels all over the world to gather data about ocean life – compiling records of what lives at different depths and how these creatures would be impacted by drilling.

Often I was the only woman on the survey ship. I’d be working along 40 or so great burley blokes. In situations like this, you have to become one of the lads, gender doesn’t really come into it. You work intense 12-hour shifts that start at midnight or midday.

Life at sea is far from glamorous. The accommodation is basic and gales can bring on horrendous seasickness. But there are magical moments too. One of mine was watching 20 or so humpback whales migrating with their young and discovering a coral reef off Mozambique, all on one trip.

Out on the ocean, I had to maintain all my equipment. That included fixing things if they went wrong. Like a complex underwater deep-water and baited camera system, water profile sensor and core sampling equipment. I compiled manuals of problems and how to resolve them. Nothing fancy – just scribbled notes and diagrams.

After six years of working offshore, I needed a change. The work was stressful and unpredictable – I once had 45 minutes’ notice to get ready for a six-week stint at sea. I was missing out on social life as I’d never know where I’d be next.

I’m a hands-on person who thrives on practical challenges. If I hadn’t been a marine biologist, I probably would have trained as an engineer. My husband is brilliantly supportive. He’s also a marine biologist - and he too wanted a change. We sent CVs to prospective employers.

I got a call from the Engineering Department. I went in for an interview with no idea of what it would be like. I found myself talking to a group of friendly people and thought “I like this”. But I wasn’t quite right for the role they were filling.

But not long afterwards, I was invited back for an interview for another role.

The interviewers were impressed by my self-made manuals. They showed that I could think through problems and put things across well, teaching myself a new discipline. I remember being asked ‘Why the change from biology to engineering?’ but this change seemed perfectly natural to me and followed on from all my years fixing things.

My job is all about encouraging students to learn new skills and try their hand at something unfamiliar. Failure doesn’t matter. Our students learn fast and come up with some fantastically creative ideas. I sometimes have to stop myself from being overly excited.

The Dyson Centre has amazing facilities. The equipment we make available to students ranges from 3D printers of all types to plasma cutter and computer numerical control machines. Students learn quickly to make anything from a 3D printed piggy bank to a jumping robot. It teaches them what’s possible.

I do miss the sea but don’t regret my decision for a moment. I’d love one day to have a role that combines engineering and marine biology. But I feel incredibly fortunate to have this job and work in such a dynamic environment where no two days are the same.

My parents are still furious that my teachers never apologised for being so wrong about me. Something my mum once said is imprinted on my brain. It was: “However big a leap you take into the plunge pool, you’ll always come back to the surface.” Jump high and dive deep.

This article is part of the This Cambridge Life series.