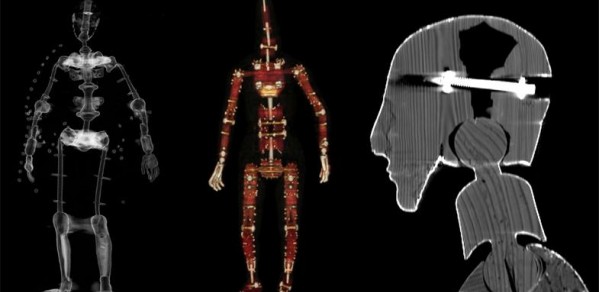

The fascinating results of Computerised Tomography (CT) scans performed on two mannequins from the 18th and 19th centuries have revealed astounding stories which may impact on the future of clinical practice.

Looking at these mannequins you can see the incredible drive to create a more accurate model of the human body and the developments that happened to allow this to take place.

Dr Tom Turmezei

The historic mannequins are from the exhibition Silent Partners, currently on display at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

The scans were taken at Addenbrooke's Hospital, part of Cambridge University Hospitals, to discover the internal workings without damaging the mannequins. At the same time, radiologists and engineers were able to use the data from the non-human bodies to test not yet clinically approved software on the images, furthering research for potential clinical practice in the future.

The procedure was led by Dr Tom Turmezei, of the Department of Engineering’s Medical Imaging Group. Tom said: “The mannequins contain both natural materials and worked metals, making for an interesting human analogue. Humans are getting more and more artificial metal parts in their bodies, for example in joint replacements, clips and plates. When these are scanned with the CT machine it creates a starburst effect in the final image, called an artifact, and this bright white flare-like trace obscures details in the surrounding tissue. Clinically this can be a big problem as it can make it difficult to perceive both damage to the metal part and any disease in the tissue around it, such as an abscess, blood clot or tumour. As we are moving towards more metallic, electronic and even robotic body parts, being able to reduce the artifact in the scan is ever more important.”

Tom was assisted by Dr Tristan Whitmarsh, also of the Department's Medical Imaging Group, who used Metal Deletion Technique software from Revision Radiology on the scans to look at the effectiveness of the algorithm to reduce the artifact.

The two mannequins scanned were ‘Child no. 98’, a high quality 19th century Parisian stuffed lay figure from the Hamilton Kerr Institute, and an 18th century, largely wooden mannequin once belonging to Walter Sickert (1860-1942) from Bath Spa University.

Alongside these mannequins, the exhibition tells the fascinating stories of two more historic figures: a 68cm tall figure from the Museum of London once belonging to the sculptor Louis-François Roubiliac (1695-1762) which was scanned separately to reveal an internal ‘skeleton’ made of saying iron, bronze and brass; and how three specialists restored a 19th century figure belonging to the artist Alan Beeton (1880-1942) which had tattered fingers and a broken nose, this included a textile conservator, a modeller of medical prosthetics and a sculptress specialising in papier mâché.

Artist’s mannequins, although fascinating objects, were tools to be used in the studio: as such their history was not always rigorously documented, and today there are gaps in our knowledge about their exact manufacture. The CT scans also allowed documentation of their construction in detail, and uncovered hidden damages to the internal workings of the figures over time. A fractured left knee joint in the Bath Spa mannequin was noted so the object can now be moved safely in the future.

Tom added: “Above all, the purpose of doing these scans was art historical; to discover their material composition and construction in a non-invasive way and confirm suspicions art historians had about these objects. Looking at these mannequins you can see the incredible drive to create a more accurate model of the human body and the developments that happened to allow this to take place. The Bath Spa model is mostly wood, by the time Child no. 98 was made they had moved to a wooden skeleton and metal joinery, padded out with horse hair and hessian. A great deal of effort was taken to give Child no. 98 as accurate anatomy as possible: the body has padding inside for flank and abdominal muscles, there is padded material inside the chest to make lungs, a belly button and even glass beads under the chest ‘skin’ for nipples.”

The event is part of the exhibition Silent Partners: Artist and Mannequin from Function to Fetish at the Fitzwilliam Museum until 25 January 2015.