An interview with Dr John Durrell, newly appointed Lecturer in Superconductivity, by Philip Guildford, Director of Research

Superconductivity intrigues experts and lay people alike. Zero resistance to electricity, huge magnetic fields, and magnetic levitation are all the stuff of science fiction.

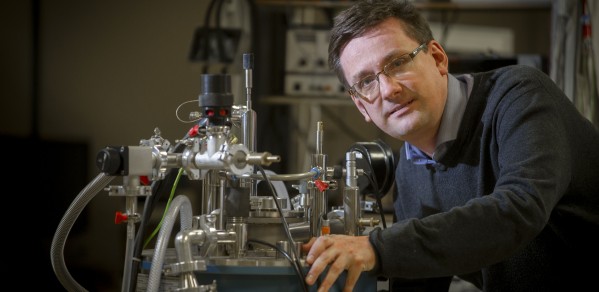

Dr John Durrell, Lecturer in Superconductivity, Department of Engineering

Philip: The discovery of high-temperature superconductivity in 1987 created a tremendous amount of scientific and media interest, but then faded from public view. What happened?

John: Superconductivity intrigues experts and lay people alike. Zero resistance to electricity, huge magnetic fields, and magnetic levitation are all the stuff of science fiction. Before 1987, it had been seen in materials at –255°C. In 1987, it was seen in new materials at –183°C. Still very cold, but can be achieved with liquid nitrogen, rather than hydrogen, and much cheaper cooling systems. Everyone got very excited, possibly too excited, with the idea of using these materials in everyday applications. It was impossible for the scientists and engineers to deliver results immediately to match the media hype and inevitably the media’s focus moved on to the next big thing.

Philip: So what progress has been made since the discovery?

John: Lots of hard work away from the media spotlight has delivered superconducting wires and materials that are used in all sorts of niche applications such as MRI scanners in hospitals, very high field magnets for research and in very sensitive devices for measuring magnetic fields. But now everything is set to move up a gear.

Philip: Why is this the moment of transition?

John: In our group in the Department of Engineering, we have got to the point where we can make big pieces of bulk superconductor with superb properties. We recently broke the world record for the magnetic field trapped in a lump of superconductor (J H Durrell et al 2014 Supercond. Sci. Technol. 27 082001 http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0953-2048/27/8/082001). We have an industrial process for producing this material. This opens the door to using much higher magnetic fields in more everyday applications such as motors and generators. For instance, we can now imagine ordinary commercial ships running with superconducting in the engine room. Mark Ainslie in our group is working on prototypes right now which we expect to be only 25% of the bulk of a conventional motor. In addition, Suchitra Sebastian and colleagues in the Cavendish Lab in Cambridge have revealed a theoretical basis for explaining why the materials we use superconduct that could accelerate our hunt for even better materials. The combination of practical industrial processes for making the materials, practical prototypes and a strong theoretical foundation creates this moment of transition in our field.

Philip: What lies ahead?

John: The hard graft of building greater understanding, improving materials, scaling up production and making it all robust enough for industrial use. As we work closely with companies, progress to market will leap forward and probably in unexpected directions, as the interface between academia and industry often generates the exciting unforeseen opportunities.

Philip: And for you personally?

John: I feel privileged to be looking after Professor David Cardwell’s group for five years while he is Head of the Department of Engineering. I want to do much more than just be the caretaker. I want to maintain the momentum that David has built over the years, keep the team spirit, develop our industrial connections and really make the most of this turning point for superconductivity. After five years, I want David and the team to be really proud of our results: new scientific and engineering discoveries, demonstrations of superconducting machines and companies working with us to take superconductors into new practical applications.