Technicians have been a pivotal part of Cambridge's ground-breaking research for centuries, yet their work is largely invisible to the outside world. Some of these unsung heroes share their experiences.

Technicians are very important. If you look in labs, technicians are everywhere, but when you look at published papers, you never see them.

From gravity to pulsars, Cambridge ideas have changed the world, and from Isaac Newton to Jocelyn Bell, its scientists' achievements are celebrated. But in the stories we tell about how this knowledge was made, a crucial collaborator in the scientific process is missing. The technician.

Today, Cambridge has 800 technicians who play a vital role in teaching and research. Their work, however, remains largely invisible, says Dr Josh Nall, Curator of Modern Sciences at the Whipple Museum.

“Historians of science are like criminologists. We're trying to understand – slightly removed from the process itself – how science works,” he explains. “As a result, technicians are very important. If you look in labs, technicians are everywhere, but when you look at published papers, you never see them.”

Looking at the Whipple's collection provides some clues – like the hundreds of intricate evacuated tubes made by glass blowers at the Cavendish Laboratory for JJ Thomson's research. But they only offer a fleeting glimpse of the technician's skill. “The material we have has the fingerprints of technicians all over it. But it doesn't take us very far, because we have no way of knowing which technician made it.” says Nall, “Historians of science in 100 years would be incredibly grateful if we interviewed or filmed today's technicians at work.”

Technicians at work

From his eyrie high above the workshop, Alistair Ross, manager of the Design and Technical Services Division in the Department of Engineering, has a bird's eye view of the dozens of machines and 25 technicians for whom he is responsible – and in whose work he takes great pride. “The skills we have here are extraordinary,” he says. “These main workshops are a central resource, and the range of things we make is – well, the sky's the limit.”

Current projects range from aero engine blades for the Whittle Laboratory to components for earthquake research at the Schofield Centre. “Anyone can come and ask me for a rig to be made – very often it’s something that's never been made before – and we find a way to do it,” Ross explains. “That's where we win: our quality, our cost effectiveness and our huge versatility compared to outside companies.”

During 30 years in the job he has developed a keen nose for a good technician. “I'm less impressed by qualifications and more interested in people's enthusiasm for life and for engineering, their hobbies and interests,” he says. “That tells me they have an enquiring mind.”

Ross's own hobbies include classic cars, restoring furniture and mending mechanical watches. “I love machines, and I can't stop making or mending things. I'd always rather buy something broken and fix it – there's nothing worse than buying something that works,” he says.

One of Ross's recruits is Barney Coles, a manual machinist who arrived at the University with little on paper but bags of enthusiasm. “I learned lots from my Dad – he builds model locomotives – and I started looking into digital ignition for a jet engine when I was in my early 20s,” he says. “That evolved into making humungous Tesla coils in my bedroom, until my parents asked me to stop because it was disrupting the TV. I don't own a telly now, but I watch machining videos on YouTube.”

He is currently making exquisite aluminium aero engine blades (“works of art”, Ross calls them) for Rolls-Royce experiments at the Whittle, turning single blocks of the shining metal into complex blades with extraordinary precision.

“What's really annoying is that there are no flat edges on them,” Coles explains. “Nothing's parallel, so you can't just put them in a vice. So I designed a unique fixing and holding system that means we can manufacture these parts in a single operation.”

It's hoped that using the blades in experiments at the Whittle will enable Rolls-Royce to produce more efficient engines, cutting fuel costs and carbon dioxide emissions. “Before I came to Cambridge, no-one was doing this. I've been on the project for two years and am quite proud to be a part of it,” he adds.

From silver to concrete

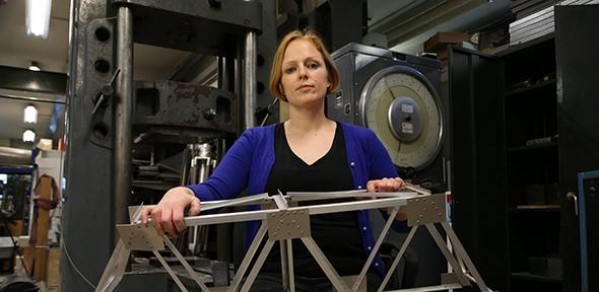

Lorna Roberts (pictured) arrived in the Structures and Concrete Lab in 2015. One of only two female laboratory technicians out of 90 in the Department of Engineering, she decided to become a technician after studying jewellery making – a craft she thinks has much in common with engineering.

“Lots of the tools are similar – although they're larger here,” she says. “But the practicalities are the same: you're given a design and you've got to make it work, fit pieces together to make something happen. I'm a problem solver – that's what I've discovered doing this job.”

She works with postdoc Dr Pieter Desnerck, who is studying the way that the reinforced concrete bridges built around the UK in the 1960s are deteriorating. Concrete is poured into large wooden moulds and fitted with strain gauges. “Then we apply the load,” says Roberts, “take all the readings, and continue until the concrete fails, which can be quite loud and quite dramatic.”

The research is giving her ideas for jewellery, too: “I found some old concrete samples the other day that were being thrown away, and when you chop them open they're really beautiful, so I kept a piece and I'm thinking about making some concrete jewellery.”

Chief laboratory technician Franco Ussi also joined the University last year. Brought up in Carrara, Italy, he has a degree in mechanical engineering and has worked in many industries, from robotics to medical devices.

At the Institute for Manufacturing he supports researchers and PhD students, fixing machines and designing instruments for experiments, and is now developing reactors to create carbon nanotube fibres in the Department of Materials Science & Metallurgy.

“My job is mainly about helping others to solve problems. My interdisciplinary experience means I can usually help them find better solutions – I'm like the link between their ideas and the final prototype,” he explains. “It's interesting to start from theoretical ideas, add practical problems and then together we find a solution – that's what's so amazing about working here with researchers.”

Apprenticeships

The University has introduced a technician development and apprenticeship project to ensure that Cambridge scientists and technicians can continue to change the world. Six new apprentices are joining the University this autumn.

Further information on technician development and apprenticeships can be found on the Personal and Professional Development website.