Cambridge researchers have become the first to combine multiple image types – RGB (that mimics human vision), depth and infra-red – in a 3D camera set up to monitor premature babies in neonatal intensive care. The aim is to provide a second set of eyes for nurses through continuous visual monitoring of the babies’ behaviour.

Our 24-hour recordings offer a better representation of the real-life NICU environment. Accurate pose estimation can contribute to the early detection of developmental abnormalities and ongoing monitoring of premature babies’ health.

Dr Alex Grafton

The neonatal period (the first 28 days of life) is a critical time with an increased risk of short- and long-term complications. In the UK, more than 90,000 babies – approximately one out of every seven – are admitted to a neonatal unit every year.

The highest dependency patients are cared for in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). In the NICU, specialised round-the-clock care is required from a team of experts, but with so much pressure on nurses’ time as they juggle responsibility for multiple babies, prepare feeds and carry out other clinical duties, continuous visual monitoring is not possible.

To address this monitoring gap, researchers harnessed machine learning technology and pose estimation – a computer vision task that uses AI to automatically track key points (in this case the hips and shoulders) – to monitor the position of 24 babies across the full range of clinical imaging scenarios. The data includes multiple 24-hour recordings during which nurses were instructed to continue delivering care as though the camera was not present. The findings are reported in the journal npj Digital Medicine.

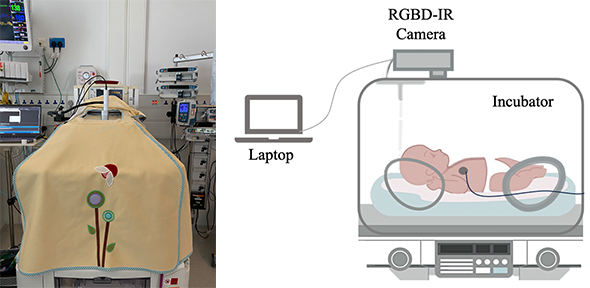

[LEFT] Experimental setup in the NICU, showing a covered incubator with the camera visible through the hole in the cover. [RIGHT] Schematic diagram of the recording setup

A neonatal incubator is a busy and varied environment, with monitoring equipment, blankets, clothing and nurses’ hands cluttering the scene, making pose estimation challenging.

The research team, led by Dr Alex Grafton, recorded babies in the NICU at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, using a calibrated RGB, depth and infra-red camera system during one-hour and 24-hour sessions. The 24-hour recordings included real interventions, light changes, movement and interactions with parents.

Machine learning allows the researchers to extract via a computer information from video footage collected of each baby. This means that interventions (such as when staff or a parent’s hands are in the cot) can be detected in real time, along with the ability to automatically locate the baby in the video frame and monitor the baby's behaviour.

Combining all three image types allows for detailed images to be captured even when incubators are covered or the room is dark.

The simplest imaging conditions are when the babies are uncovered or half-covered, but this only accounts for approximately half the time. The babies spend a lot of time covered, or lying on their sides, which makes imaging difficult.

The findings showed that for uncovered and half-covered babies, the researchers’ machine learning models recorded better than average human performance. This was also the case for babies lying on their backs and stomachs. However, for fully covered babies, or babies lying on their side, the model scored worse than average human performance.

“This clinical study was a chance for us to try something new, with our 24-hour recordings offering a better representation of the real-life NICU environment,” said co-author Dr Grafton, Research Associate in Non-Contact Neonatal Monitoring. “Accurate pose estimation can contribute to the early detection of developmental abnormalities and ongoing monitoring of premature babies’ health. These advancements offer valuable insights that can inform clinical decisions and interventions, ultimately improving the standard of care for newborn babies.”

He added: “No existing dataset includes images of babies in the presence of blanket coverings or clinical interventions. Understanding the performance of these algorithms in this environment is needed to demonstrate feasibility for continuous clinical use. Our study offers an alternative approach combining RGB (standard colour images that rely on external light), depth (which works well in the dark and offers three-dimensional information) and infra-red (which also works well in the dark) for real-time analysis of neonatal pose estimation. These models are based on retraining from machine learning models originally trained for pose estimation in adults, which is a much more well-studied task.”

Co-author Dr Joana Warnecke, a former postdoc in the Department of Engineering, said: “We found that using all three image types gave better results than just one image type, and we were also able to use smaller models for the multi-image methods. Space is at a premium in the NICU, so simpler models means that we can use a smaller device. We were expecting some of the decreases in performance due to covering and position, but these imaging scenarios generally have not been covered in previous studies, so it was important to quantify them. If we want to develop something useful for real clinical practice, it is important to test methods on the entire range of clinical scenarios, not just the ‘easy’ images.”

Co-authors Dr Joana Warnecke (left) and Dr Alex Grafton demonstrating wireless vital sign monitoring of premature babies alongside a staff member from Cambridge Newborn Research.

This research is part of the Meerkat project, a collaboration between the Departments of Engineering and Paediatrics, which aims to develop intelligent, non-contact monitoring to support care delivery in the neonatal unit. Dr Grafton and Dr Warnecke carried out this research with support from nursing staff on the NICU at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, and were supervised by Professor Joan Lasenby and Dr Kathryn Beardsall.

The researchers will now turn their attentions to testing vital signs monitoring such as heart rate and respiratory rate using the 24-hour recordings. They will use low-frequency pose estimation to locate the baby each second.

Also in the pipeline is the development of a neonatal-specific scoring system based on the babies’ images that have been labelled by clinical staff in this clinical study. The current system is based on how well non-clinicians label images of adults. The researchers would also like to extend this system to detecting motion of arms and legs.

And finally, a focus on movement detection – monitoring how the babies move is important for assessing their development. Expert staff are trained to do these assessments; however, they must often monitor long periods with no movements to find out what to look for. Using continuous monitoring, the researchers can detect periods of motion – good or bad – that may be of interest to staff; to help staff monitor the baby so that they can spend more time doing their expert role, as well as making these assessments available to more babies.

Reference:

Alex Grafton, Joana M. Warnecke et al. ‘Neonatal pose estimation in the unaltered clinical environment with fusion of RGB, depth and IR images’. npj Digital Medicine (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41746-025-01929-z